How Does The Coronavirus Epidemic Ends – The worst-case scenario for the outbreak in the United States is if there are sudden spikes in infections among many communities across the country. A spike could overwhelm our health care system.

“That’s one of the most dangerous things about this,” Ron Klain, who led the response to the 2014 Ebola epidemic under the Obama administration, said in February. “What if all of a sudden 10,000 sick people needed hospitalization in a major city? There’s no 10,000 extra beds sitting around someplace.”

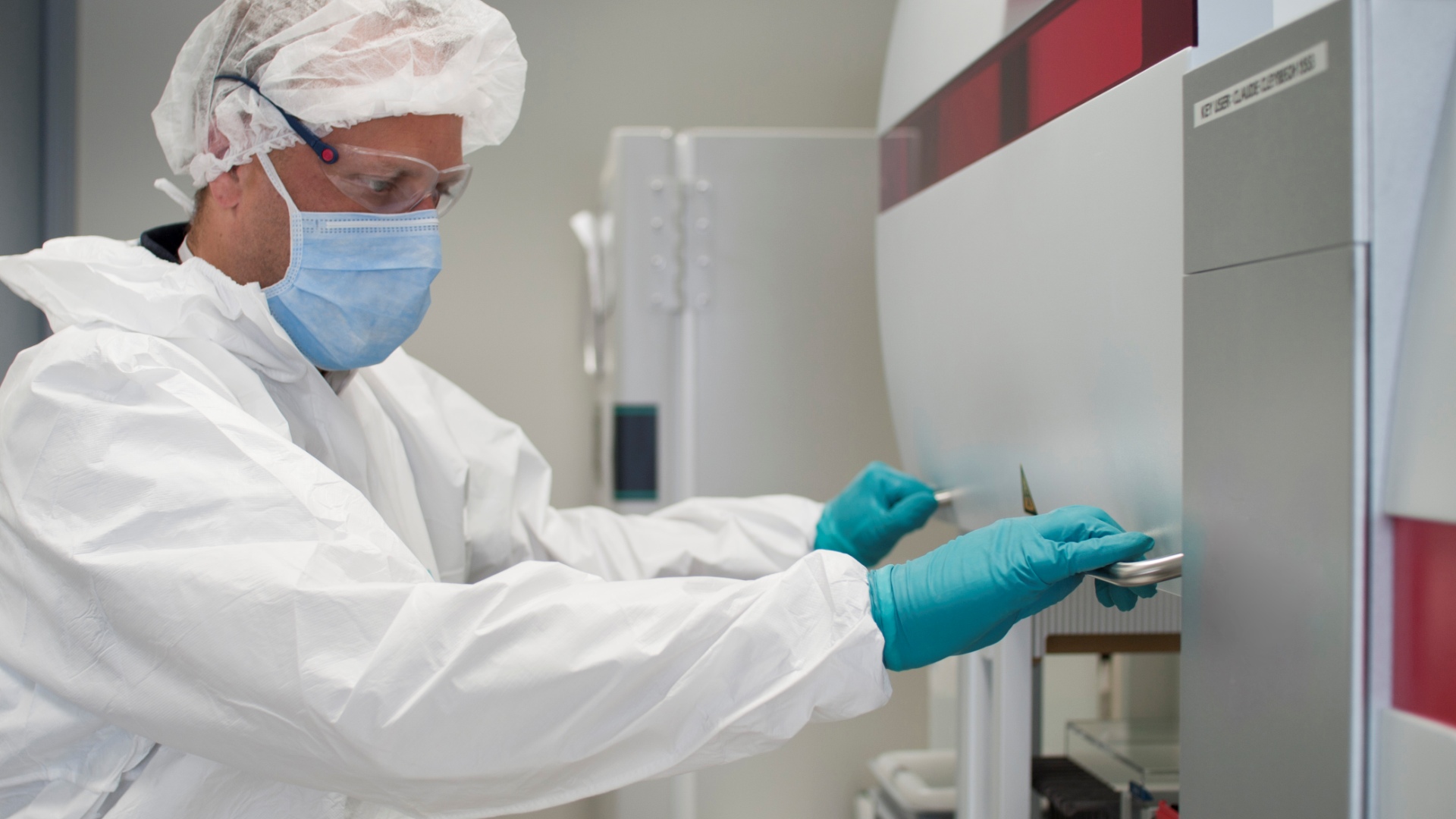

Hospitals are already worried about equipment shortages. And as sick people rush into the hospital system, they could infect health care workers — as well as other vulnerable patients, particularly the elderly — leaving the system in even more dire straits.

RELATED: America Unprepared For Coronavirus Wave

“We saw in Wuhan 1,000 health care providers get sick and we had at least 15 percent severely ill and in ICUs,” Peter Hotez, a vaccine expert with the Baylor College of Medicine, testified before a House committee Thursday.

“And that is very dangerous, because not only do you subtract those people out of the health care workforce, but the demoralizing effect of colleagues taking care of colleagues … the whole thing can fall apart if that starts to happen.”

But this nightmare scenario isn’t inevitable.

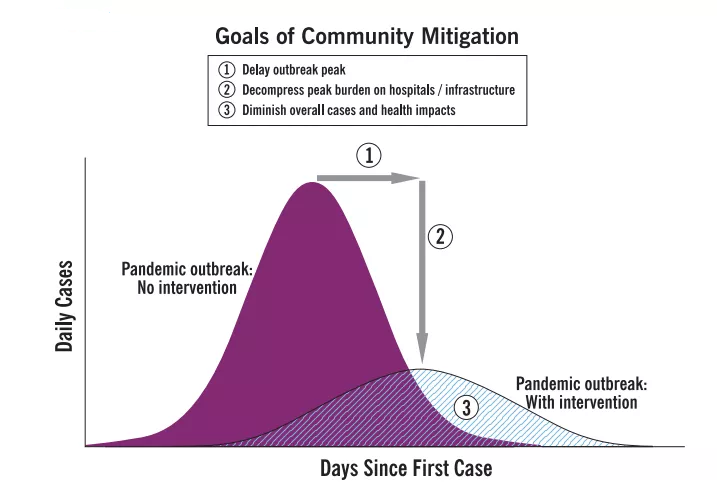

“If we slow it so that infections happen over 10 or 12 months instead of over one month, that’s going to make a big difference as far as how many people seriously infected, how many people may end up hospitalized, and how many they end up dying,” Smith says.

“We talk about it as ‘flattening the epidemic curve’ — so that it’s not a big, sudden peak in cases, but it’s a more moderate plateau over time.”

Flattening the epidemic curve, in one chart. CDC

And that’s the current goal: to flatten the curve.

Public health measures slow the spread and buy scientists time

New cases in China are now declining thanks to the government’s dramatic measures to contain the virus — mainly case finding, contact tracing, and suspension of public gatherings — as WHO epidemiologist Bruce Aylward, who led a recent mission there, told my colleague Julia Belluz.

In the US, there’s still time to put those efforts in place to flatten that curve.

In Washington state, health officials are now asking community groups to cancel events that bring together more than 10 people, and are recommending that people telework if they can.

Pregnant people, people older than 60, and those who have underlying health conditions are being asked to stay home. More states and communities may have to impose such measures in the coming weeks. So be prepared for them.

“We also need to stop panicking and stigmatizing people of different ethnicities— this will only make people more hesitant to speak out and seek care,” says Abraar Karan, a physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School. “Disease should show us that we are all connected and need to help each other, not divide us.”

Individuals can help slow the spread of the virus through measures like staying home when you feel just a little bit sick (even when it is inconvenient), washing hands often, and following public health official recommendations when it comes to avoiding large crowds of people.

That’s the optimistic take: We will slow the spread, and help out our communities and the most vulnerable in the process.

The pessimistic view: Because of the lag in testing, the outbreak might be further along — and therefore harder to contain — than authorities currently realize. “There certainly is a window to [impose social distancing measures], but whether or not we’re still in that window, we have no idea because we have no idea what’s happening without the testing,” Grubaugh warns.

Covid-19 naturally stops spreading as fast during the summer

Another factor that could potentially slow the spread of coronavirus is the changing of the seasons.

For a variety of reasons, some viruses — but not all — become less transmissible as temperatures and humidity rise in the summer months. The viruses themselves may not live as long on surfaces in these conditions.

Also, human behavior changes, and we spend less time in confined spaces. “A lot of how the outbreak ends or at least how things progress in the next few months really depends on if this is seasonal,” Grubaugh says.

That’s still a big unknown. “Just because some respiratory diseases, like flu, demonstrate seasonality doesn’t mean that Covid-19 will,” Maimuna Majumder, a Harvard epidemiologist, says.

She and colleagues recently published an early version of a paper (which has not been peer-reviewed) that found that changes in weather across China did not seem to impact the course of the outbreak.

The study suggests that humidity — which appears to be correlated with the seasonality of the flu — is not correlated with transmissibility of Covid-19, she says. (She also stresses to treat the data as “provisional,” and that her group is still studying the potential effect of temperature on transmissibility.)

But if it is seasonal, it doesn’t mean Covid-19 goes away after the summer. “It likely isn’t just going to magically go away,” Grubaugh says. “Next winter might end up being the big winter.”

And if it is seasonal, it’s still dangerous. It would be like the flu, “except potentially with a higher case fatality rate,” Rasmussen says. “Which is definitely a problem because the seasonal flu kills 30,000 to 60,000 Americans every year. And even if it’s the same case fatality rate of seasonal flu, that still presents a substantial public health burden.”

How this outbreak could truly end: With a vaccine

To end this outbreak, for good, we’ll need antiviral treatments or a vaccine. Those are currently being produced, and at record speeds. Researchers are working on new vaccine technologies — like mRNA vaccines that don’t use viruses at all in their production process — as well as cutting-edge therapeutic antibodies.

That said, it still could be a year or more before the safety and efficacy of these pharmaceuticals are proven. In medicine, effectiveness is not guaranteed.

But even if it takes a year or more to produce, those treatments could still prove useful.

“We don’t know what’s going to happen with this virus,” says Barney Graham, the deputy director of the Vaccine Research Center at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). “So our job is to try to develop interventions that could be used if it gets worse. … We need ways of protecting ourselves.”